“Peaceful war made against the enemy in your workshop is no less efficacious than the war waged on battlefields”

– Napolean Bonaparte

In a post-war era where, for the most part, patriarchal emphasis was still on women creating a home; the Greenham Common Women’s Peace March subverted society’s expectations, when women applied their home economics skills to protest against storing nuclear weapons in the UK.

Where women were expected to be submissive and conform to gendered roles in the domestic sphere; women found strength in their crafts and accomplishments, found their voices and marched. 30,000 women with homemade, colourful banners adorned with slogans and signs of peace, 30,000 women marched in protest against the UK government.

Perpetuating the female gendered role in an unexpected setting, these women built camps around the fences of the common, they created communities, they cared for one another, they cooked and made each other clothing, and lived there for 19 years until, eventually they were successful in their cause and the bombs were dismantled.

“Greenham women’s oversized, hand-knitted jumpers were… instrumental in taking knitting out of the private, domestic sphere and making “women’s work” public.” Textile, Cloth and Culture (p3).

Throughout my research I saw illustrations and references to spiderwebs, something I don’t instinctively associate with being feminine. The women at the camp were known to create ‘spiderwebs’ amongst themselves, using wool to tie themselves to each other, the chain link fences and vehicles at the base, to confuse and slow down police officers that were trying to detangle them.

“The spider web became one of the most-used symbols at the camp, because it is both fragile and resilient, as the Greenham women envisioned themselves.” Fairhall 2006, pp. 40–41

Remembered for their crafts and knitwear, the Greenham women created these remarkable banners that now reflect a narrative of their time at the camp. “The women recognised that “the gesture of creativity itself was a gesture of non-violence” (Lesperance 2020, 4), they were interested in the act of creating, not destroying.” Textile, Cloth and Culture (p3)

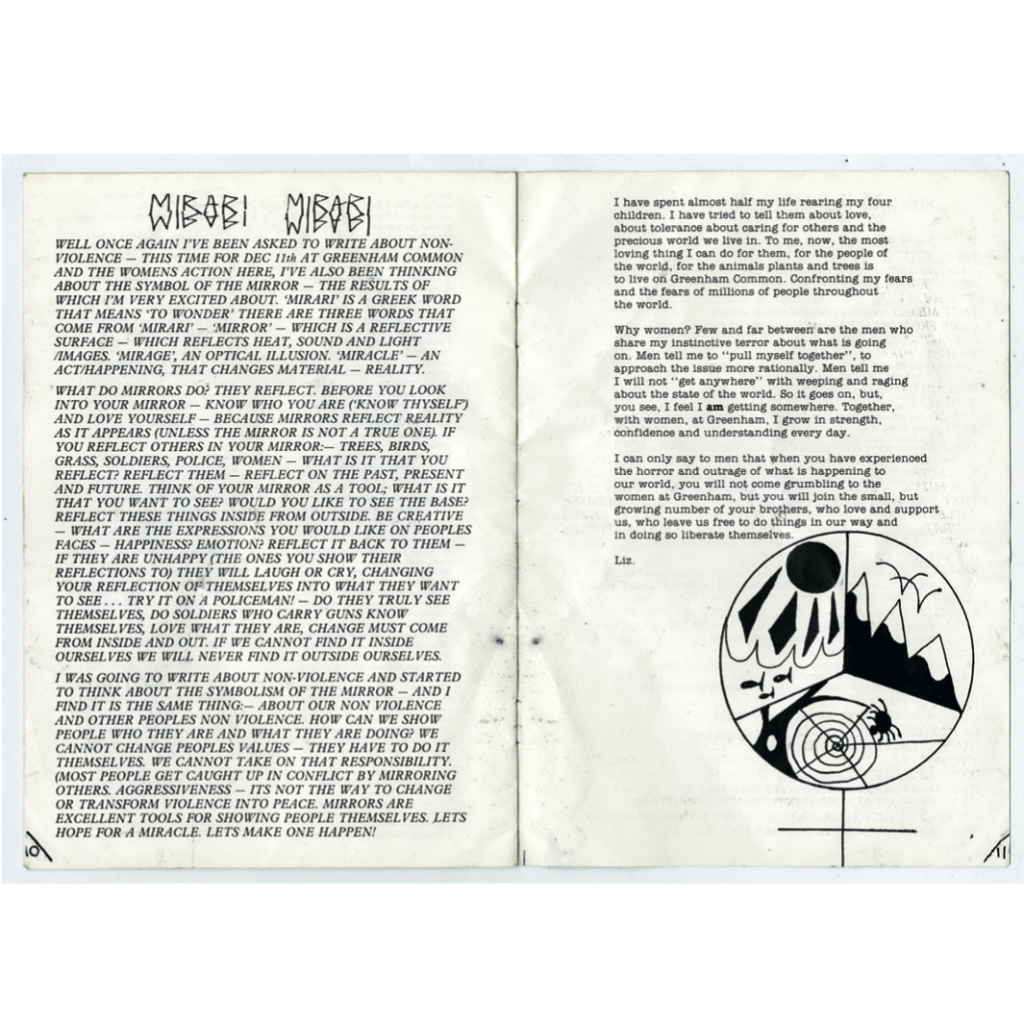

Whilst researching the Greenham Common Peace March I discovered a reference to a booklet ‘Women Reclaim Greenham, 11 December 1983 (pg 10 & 11) in Liz Murray’s thesis, (p179) which reads :

“I was going to write about non-violence and started to think about the symbolism of the mirror- and I find it is the same thing: – about our non-violence and other peoples non-violence. How can we show people who they are and what they are doing? We cannot change peoples values – they have to do it themselves. We cannot take on that responsibility. Most people get caught up in conflict by mirroring others. Aggressiveness – it’s not the way to change or transform violence into peace. Mirrors are excellent tools for showing people themselves.”

– Liz

This resonates with how I feel towards educating people about the fashion industry. The hope is that, when having a better understanding of the lifecycle of clothing, people will make more considered, conscious and sustainable decisions around their existing wardrobes and future purchases. But as an individual, I can’t change peoples values or take on that responsibility.

Feature image

Women Reclaim Greenham, 11 December 1983: pages 10 and 11 of booklet produced by CND for the GCWPC for distribution to the 50,000 women protesters who encircled the airbase on 11-12 December 1983.

Referenced from Murray, L (2001) (see below.)

References

Fairhall, David (2006). Common Ground: The Story of Greenham. I.B. Tauris.

Textile, Cloth and Culture (9 November 2022) Will There Be Womanly Times? Reflections on the Work of Ellen Lesperance. https://hollybushgardens.co.uk/files/ellen-lesperance-textile-cloth-culture-nov-2022.pdf

Murray, L (2021) Performing Resistance; The Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp as Artwork.

Leave a comment